Can Netflix Create an Original Sport?

Join thousands of savvy investors and get:

- Weekly Stock Picks: Handpicked from 60,000 global options.

- Ten Must-Have Stocks: Essential picks to hold until 2034.

- Exclusive Stock Library: In-depth analysis of 60 top stocks.

- Proven Success: 10-year track record of outperforming the market.

Key Takeaways

- Netflix propelled Formula 1 to new highs but most of the monetary success didn't benefit the streamer. Learning from this mistake, Netflix seems eager to own a sport outright.

- Live entertainment is the last stronghold for linear TV's ad dollars. 31% of the segment's money is generated from live sports. With more streamers looking for ad-supported revenue and Netflix's large cash pile, an acquisition doesn't seem out of the question.

- The popularity of Netflix assets such as Stranger Things, The Queen's Gambit, and Wednesday begs the question: Will the first streamer look to convert its IP into more lasting investments?

A Laughing Matter

One of the greatest shows of the last decade was Mad Men. Created by Matthew Weiner, one of the writers of The Sopranos, Mad Men spent seven seasons following a group of Madison Avenue executives, headed up by Don Draper, in 1960s New York. It has all the alcohol and debauchery you would expect but it’s also a great look into the golden age of advertising and the nature of business.

Among its most memorable episodes is Season 4, Episode 3: “The Arrangements”. Thematically, it explores the concept of reinvention, breaking from tradition, and the desire to forge one’s own path. The art department is shooting a commercial for Patio, a new diet soda from Pepsi targeted at women, while Draper contends with his father-in-law’s looming presence. Even young Sally contributes to the motif, reading her grandfather The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

However, no plot line is as poignant as Horace Cook Jr.’s arrival at the Sterling Cooper offices. Cook is the heir to a large shipping fortune and has never worked a day in his life but he’s hoping to change all that and go out on his own. He’s come across a new sport, or rather an old sport that hasn’t yet made it big in America called jai alai. Exceedingly popular in France, Spain, and large swathes of South America, Cook is certain he can use his fortune to launch a jai alai league in the United States and create a “new national pastime”. He dreams of gifting his father a team to finally win his approval.

Overall, it seems pretty ludicrous and that’s exactly what the executives of Sterling Cooper thought. They take Cook for all he’s worth, referring to the heir as “the fatted calf” and billing him more than $1 million before jai alai ever makes it onto American airwaves.

It takes Cook a while but he eventually fires Draper and his colleagues for failing to take jai alai seriously.

Drive to Thrive

Launching a new sport in the United States is no small feat. With the likes of football, both college and professional, basketball, baseball, ice hockey, soccer, boxing, golf, and NASCAR, the scene seems pretty full. But that hasn’t stopped Netflix from creating powerful sports stories in some unlikely places. In 2016, the streaming giant launched Last Chance U, a documentary series that followed East Mississippi Community College’s football team.

East Mississippi is one of thousands of junior colleges in the U.S. so it took a lot to make the nation cheer for them. Netflix accomplished this by focusing on the details and the people behind the jerseys and pads. You learn the back story of many of the team’s key players; their hardships, plans for making it to the next level, and love of the game. All of this builds an emotional connection between the audience and the team and makes up for the fact that none of us could place East Mississippi on a map. You don’t need nostalgia or a family connection to cheer for this team. Netflix replicated this feat a few years later with Cheer, which followed a junior college cheerleading squad over the course of a season.

More impressive than both these productions though, was Formula 1: Drive to Survive. The ten-part series, made in collaboration with Formula 1, followed the 2018 World Championships, giving viewers an inside look at “the cockpits, the paddock, and the lives of the key players”. Formula 1 seems like a sport especially made for this format as each race is the culmination of weeks of planning, engineering, budgeting, and yelling. To quote Carrie Battan, a contributor at The New Yorker:

“The racing world is rife with idiosyncrasies that seem almost as if they were created to drum up controversy. The sport has ten teams of car manufacturers, each with two drivers. Each team’s budget and resources vary wildly depending on how much sponsorship it can generate; the more money, the faster the car, generally speaking. This means that each driver’s greatest competition is often his teammate, the only person on the same mechanical playing field. The glory-seeking pursuits of the individual drivers are in constant battle with the collective efforts of the team; this often results in fireworks on the racetrack.”

Really, race day is just the tip of the iceberg so Netflix is bringing you the other 99% of the action.

Interestingly, since Drive to Survive launched, Formula 1’s popularity has skyrocketed. Prior to the 2019 series, Formula 1 pulled in minuscule numbers in the United States. When the races were shown on ESPN they were lucky to attract half a million viewers. NASCAR, on the other hand, could draw in four million for the Indianapolis 500. There was a single race stateside, in Austin, Texas, and in-person interest was waning.

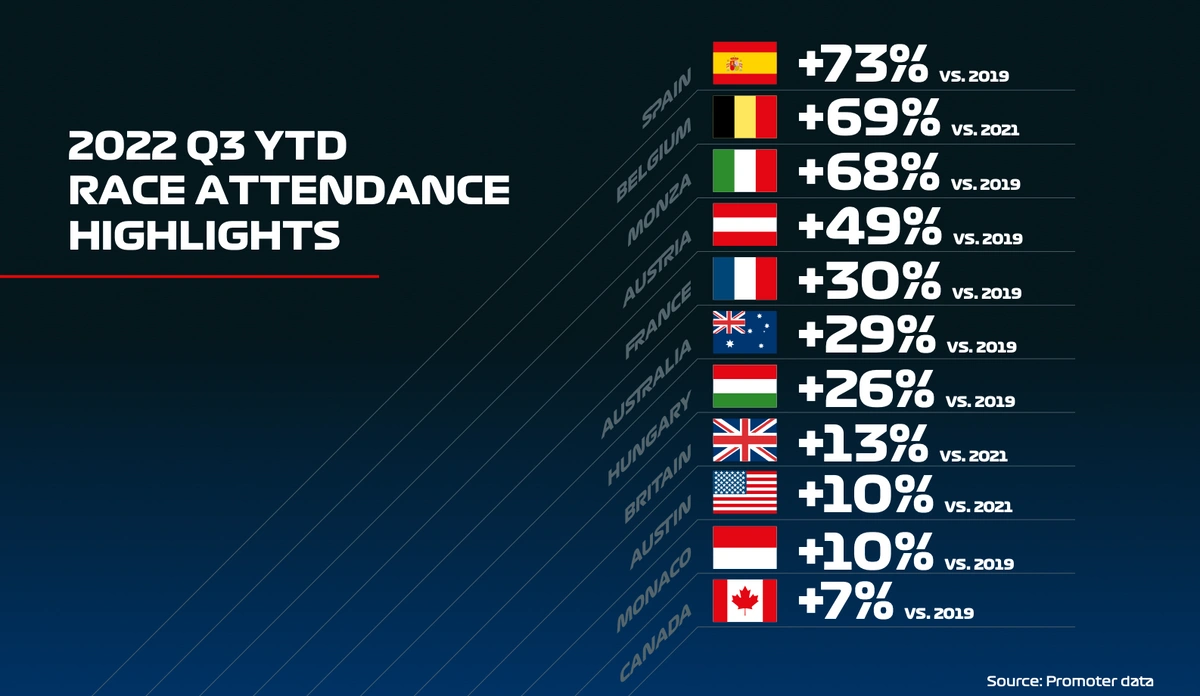

By 2022, though, viewership numbers more than doubled. Not just in the United States but globally, and ticket sales for races surged. The 2022 Austin Grand Prix became the largest event the sport has ever seen, drawing more than 400,000 fans over three days. This made the addition of a second American race a no-brainer so Miami was added to the schedule. In 2023, Las Vegas will hold a race, making the United States the first nation to host more than two Grand Prix in a single year. When fans were asked why they came to the Austin Grand Prix more than a third cited Drive to Survive.

And this relationship seems to go both ways. When season 4 of Drive to Survive premiered on Netflix this year, it became the most-watched show in 33 countries.

Failure to Thrive

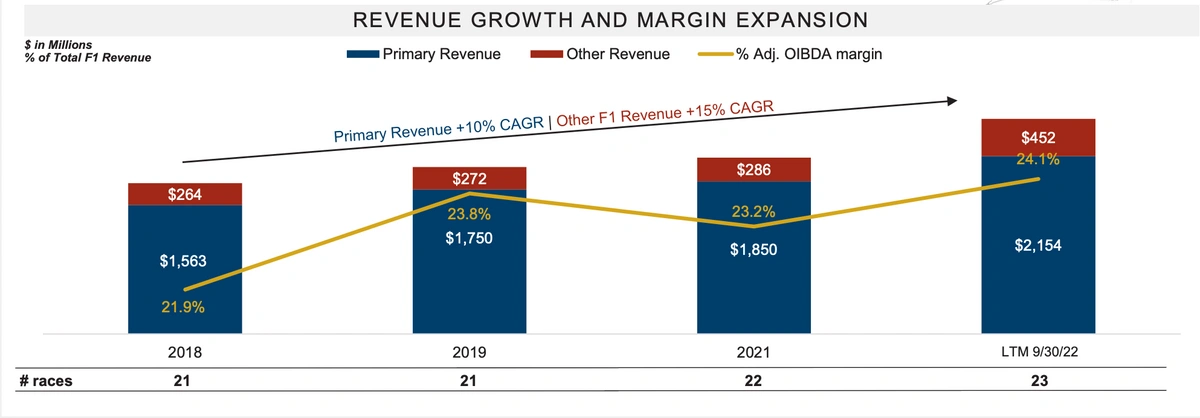

As you can see, Netflix revolutionized a sporting event and brought it back from the brink. That’s no small feat and is a testament to the streamer’s power and reach. Unfortunately, though, Netflix doesn’t make all that much from Drive to Survive while Formula 1 rakes in the cash. The league continues to control the distribution rights of races, all live events, and merchandise, meaning it definitely got the right end of the deal. Since 2018, Formula 1’s revenue is up more than 38% and the company has achieved consistent profitability. Its stock, which trades under the ticker FWONK, has doubled in that time.

So, while Netflix succeeded at humanizing a heavily technical sport and created a runaway success, it didn’t get to reap all the possible rewards because it doesn’t control the live action or the licensing rights. If it were any other type of content, a roaring success of this magnitude would mean big things for Netflix’s top line. Undoubtedly, you could expect a mobile game, team merchandise, and ticket sales — all of which would help diversify Netflix beyond its subscriber base.

Worse still, streaming rights for Formula 1 rest with ESPN which is owned by Disney. In effect, Netflix supercharged one of its greatest competitor’s assets. Co-CEO Reed Hastings and his team tried to fix this in early 2022 when Formula 1’s streaming rights came up for renewal but they eventually determined the price was too high and dropped out of the running. Hastings has reportedly stated at several board meetings that he “does not want to be in sports bidding wars every few years”.

At the end of the day, Disney picked up Formula 1’s rights for another five years for an estimated cost of $75 to $90 million annually. Prior to Drive to Survive, Disney paid $5 million a year.

Ride the Wave

Ok, now let’s talk hypotheticals. In an ideal world, Netflix would just buy Formula 1 and it would become a ubiquitous part of its entertainment package. However, a controlling interest in Formula 1 was purchased by Liberty Media in 2016 for $4.4 billion which is probably way more than Netflix would ever want to spend. The streamer’s most expensive acquisition to date is the Roald Dahl Story Company, which cost it $700 million. It aims to spend $17 billion on content in the coming years, it would be pretty risky to gamble so much of it on a single asset.

So, maybe we have to let F1 go but could Netflix recreate the magic with another sport?

Reed Hastings is hoping it can.

In November of 2022, the Wall Street Journal reported that Netflix had held secret meetings with the World Surf League in the hopes of purchasing the entire group outright. These talks eventually came to a halt, though, when the two couldn’t agree on a price. Apparently, the league loses anywhere between $10 and $50 million a year and is little more than a passion project for current billionaire owner Dirk Ziff (only a surfer could have this name).

That being said, surfing would be a great sport to get the Netflix treatment. The league takes place across the world over the course of the year and competitors come from all backgrounds and ages. It actually already has its own version of Drive to Survive on Apple TV called Make or Break but it hasn’t received the same attention. Maybe Netflix would be able to make something more worthwhile and generate some revenue.

Most importantly, if Netflix doesn’t want to participate in the great licensing rat race, creating a sport is its only option for getting its foot in the live event door which will become all the more important now that it has an ad-supported tier.

Live sports are beloved by advertisers. 31% of U.S. linear TV ad revenue comes from live sports, while the consistency of live broadcasts can keep an audience captive for months or weeks at a time, helping to curb churn. Netflix’s hesitancy to grab a piece of the sports action has understandably left some investors scratching their heads.

However, we do seem to be in a live sports land grab at the minute and that has pushed licensing costs to an all-time high. Sports rights are expected to cost $26.6 billion in 2023, up 75% from 2015. Basically, every streamer other than Netflix has jumped in and some of their price tags are mighty high. ESPN and Turner — a division of Warner Bros. Discovery Inc. — will have paid $24 billion by the time their contract ends with the National Basketball Association. Amazon pays $1 billion a year for the rights to Thursday Night Football while Youtube recently struck a deal for the NFL ‘Sunday Ticket’ at a cost of $2 billion annually.

This would explain Netflix’s co-CEO Ted Sarandos’ belief that there’s “no path to profitability in renting big sports.” With prices like those it genuinely seems more reasonable to make a sport out of thin air. As Netflix enters maturity, management has reiterated its goal of achieving consistent profitability. For now, it would appear, live sports are the antithesis of this goal so the streamer will be employing an “if you can’t beat them, don’t join them” philosophy.

The Jai Alai Life

It has been fascinating to watch Netflix take just about anything and make it popular. After the debut of The Queen’s Gambit, eBay reported a 273% increase in searches for chess sets. When season 4 of Stranger Things came on the scene, Kate Bush’s ‘Running up that Hill’ soared to number on the Billboard chart. Its latest release, Wednesday, prompted an ultra-viral TikTok dance trend and rocketed its star, Jenna Ortega, to unprecedented overnight fame. She gained 9 million Instagram followers the day the series premiered, eventually tripling her following within a week.

I believe if Netflix decided to curate a sport, it would be successful. The streamer is incredibly good at connecting audiences with all kinds of stories, I don’t think a wacky sport would be any different. They could even borrow a chapter from jai alai’s book.

While Horace Cook Jr. was laughed out of the Mad Men offices, in reality, the game became incredibly popular within the southern United States in the 1970s thanks to its luxury branding. The jai alai stadium in Miami became a place for the rich and powerful to socialize. Fans included Bob Hope, Hubert Humphrey, Babe Ruth, Jackie Gleeson, and Slyvester Stallone. Ernest Hemingway even visited and wrote about it.

Plus, if Netflix created a sport it could finally expand its revenue beyond subscriptions. If Disney made Drive to Survive, there would be a Formula 1 simulator in the Magic Kingdom by the end of its first season. Netflix is the creator of valuable IP, it’s time it gains some runway.

If jai alai has taught us anything, it’s that forging your own path can sometimes pay dividends.

- Weekly Stock Picks: Handpicked from 60,000 global options.

- Ten Must-Have Stocks: Essential picks to hold until 2034.

- Exclusive Stock Library: In-depth analysis of 60 top stocks.

- Proven Success: 10-year track record of outperforming the market.